Gerhard Moncovich, Professor of Biology

When he reached the last line of the document he crumpled the paper with his right hand and, with a grinding action of his combined hands, reduced the irregular ball to a small sphere. With a hurried motion, he hurled the paper ball into the trash, hitting the can squarely in the center, whereupon the class broke into applause and a few students in the back of the room shouted, “Score!”

Professor Moncovich, however, did not appear satisfied with his action because he retrieved the crumpled paper from the trash and patiently straightened and smoothed it, using the edge of the lecture desk to iron out the creases. He folded the paper once lengthwise, pushed it into the left back pocket of his faded jeans, turned to the class, scanned the faces of the 147 students in the auditorium. and began his lecture in a loud and commanding voice without any form of greeting.

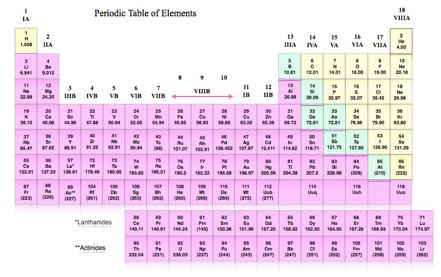

“The behavior of atoms,” he bellowed, “is determined by electronic structure—structure meaning the number and type of electrons that a given atom has. The behavior of atoms determines the behavior of molecules and the behavior of molecules determines the behavior of everything you see around you, including yourself and the students to your right and the students to your left. If you are wise enough to study biology, you will learn exactly how atomic structure leads to an understanding of the workings of life itself.”

Moncovich had protested loudly when Dean Harcross had tapped him to teach chemistry. Harcross, ignoring Moncovich’s complaints, had said, “Gerhard, you are simply the best-qualified professor we have who can fill the gap left by the resignation of Dr. Murphree. Cheer up. You have to teach chemistry only until additional chemistry faculty members can be recruited.” When his protests were consistently ignored he reluctantly refreshed his knowledge of general chemistry, which had become more sophisticated than he remembered with a heavy dose of quantum mechanics and physical chemistry

Today he was teaching atomic structure with its arcane language of “orbitals” and “wave functions.” He explained at great length how atoms with filled shells of electrons—say, those containing two or eight electrons, as in the case of the noble gases—were inert, while atoms with other configurations were reactive.

Professor Moncovich continued his lecture, “Reactions of atoms progress to reach stable electronic configurations. For example, metals lose electrons to get down to filled shells and nonmetals accept electrons to get up to filled shells.”

While he spoke those words he moved slowly up one of the aisles of the auditorium, and when he had completed the sentence, he paused at the desk of a male student who was obviously sleeping and unaware that he was the object of Professor Moncovich’s attention. In a voice that seemed to shake the hall, Professor Moncovich commanded the student, “You! Get out of my classroom! That’s right, I said get out, and don’t come back!” The student rose in disbelief and stumbled up the steps, falling once, but recovering his balance as he made his way out one of the second-floor doors.

Moncovich returned to the podium and continued, “This is important material that will serve you well in any science class you choose to take. Are there any questions?”

A blonde female student in the front row, sitting with her legs crossed at the knees and wearing a dark red skirt that Moncovich estimated to be about ten inches long from its waistband to its mid-thigh terminus, said in a demur voice, “Professor Moncovich, I just don’t get the periodic table. I don’t know how it works and I’m sure that other people feel the same way. Will you please explain it to us?”

Moncovich moved quickly toward the student and said in a voice conveying disdain, “That question should not have been asked! That question should have been answered in high school or, in progressive school districts, in middle school.”

He turned his attention to the class as a whole and, making sure that his intended sarcasm could not be missed, said, “When I saw Sleeping Beauty, I thought that this material may be too elementary to hold your interest and that all of you may have mastered it before you came into this classroom. But now I get the opposite impression altogether, that maybe it is too advanced for you.

“There’s only one way to find out, and we’ll do it the old-fashioned way, without computers or multiple choice questions. Please take out a single sheet of paper, put it on your desk, place your pen or pencil on the paper and remove all other materials from your desk. You will have exactly twenty minutes and not a minute more after I say ‘go’ to complete the quiz that I’m about to give you. I will not accept a paper from anyone who continues to work after I say ‘pencils down.’ One more thing: this quiz will count for twenty-five percent of your total grade in this course.

“I can tell you now that there will be places for only one hundred students in the second semester of this course. I’ll do the math for you. That means forty-seven of you will not be back next term, so we might as well find out early whether you’ve got what it takes to advance in science at Haney University.

“Gerhard, please allow me to pass,” Trent said, in a weak and strained voice. “You know I bear you no ill will. I don’t think you want a confrontation with me.”

“Why not? I’m certainly justified to have one,” Moncovich said. “Justified by a little piece of paper that came to me in an unmarked brown envelope, a photocopy of your diary that describes a moonlight Baltic cruise. How stupid could I be? I believed her when she said she was going on that cruise with her sister.”

“Gerhard, you’d be better off spending more time at home and less at this unappreciative university,” Trent responded.

“Don’t give me advice on my home life, you bastard,” Moncovich hissed. “I could kill you!”

Now under the full influence of the physiology of combat, Trent bellowed, “Gerhard! Gerhard, take one more step toward me and I’ll drop you with one blow and kick you five times before you hit the floor. Step aside!”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Copyright © F. Wyman Morgan 2011